By Fernando Ospina

Welcome to ERACCE’s first blog post. This blog will be a place for us to share our analysis of current issues pertaining to systemic racism and the antiracism movement. We will apply an antiracist lens to understanding what is going on in Southwest Michigan and around the nation as well. We will follow current events and reach back into history to better understand how racism and institutional oppression manifests today and in our everyday lives.

Understanding history is vital to understanding why, for example, protests against police violence are occurring today. Historical events and present-day lived experiences are not often easy to disentangle.

Using an ahistorical (without regard to history) lens, a person may easily conclude that the protests against police violence occurring today are merely a reactionary response to a series of isolated incidents, including the shooting of Michael Brown, Tamir Rice, Trayvon Martin, and several others. These “isolated incidents” are seen as the result of a few rogue police officers or vigilantes and even the fault of the victims themselves. The events are seen as if the history that led up to them does not exist. The only thing that exists is the behavior of the individuals at the moment of conflict. All that matters is the “objective” details of the events, seemingly void of context. Then, individuals who believe themselves “objective,” despite the fact that they themselves were also shaped by history and lived experiences, make decisions about innocence or guilt.

Bringing in historical context fills in the missing pieces, humanizes the individuals involved, makes analyses more accurate, and helps clarify and explain the behaviors of the moment. Protesters are not merely responding to a series of shootings of unarmed black men and teenagers, they are responding to something much bigger.

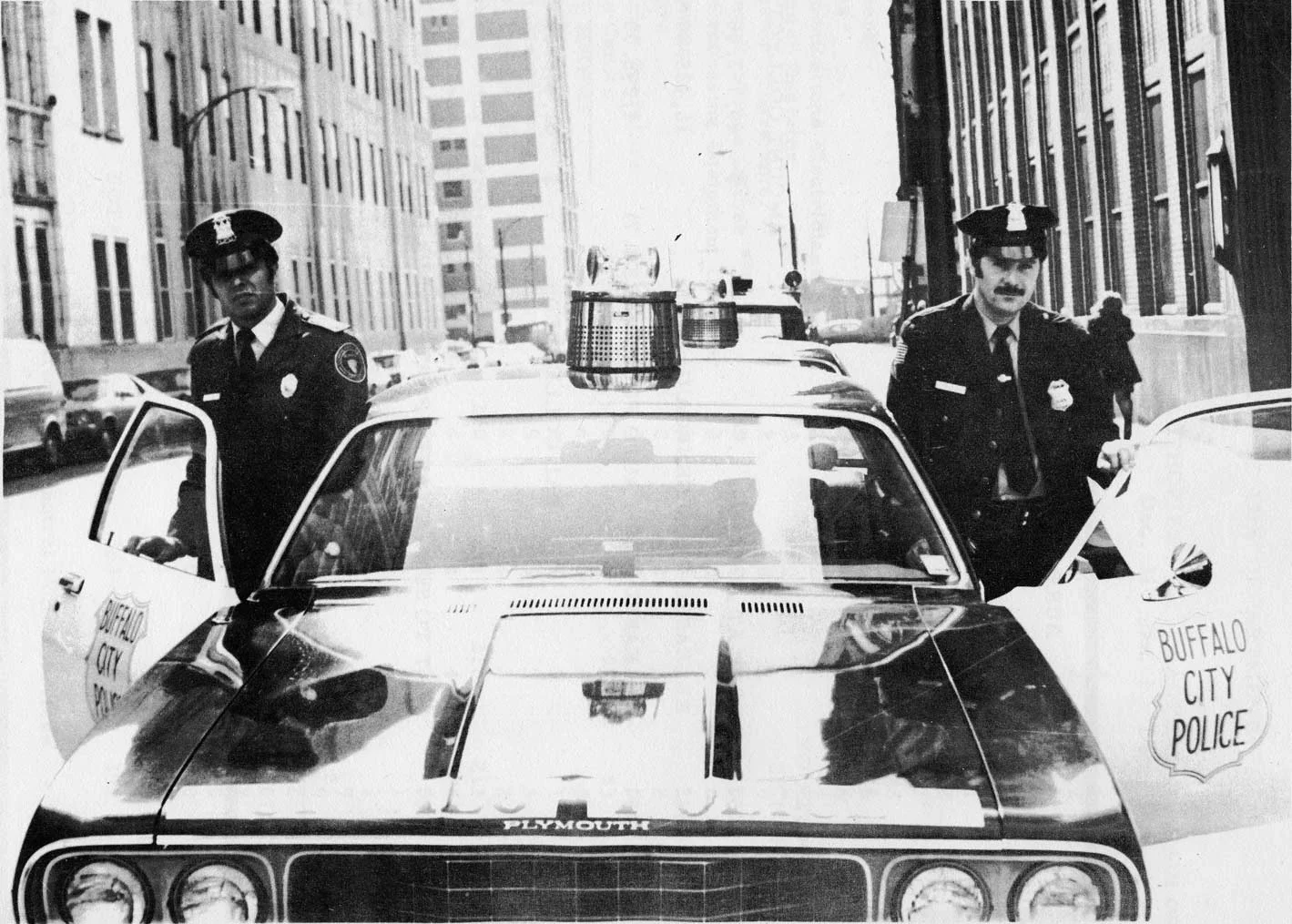

Throughout our (United States) history, law enforcement has not merely been used to “serve and protect.” Law enforcement has been used to do exactly what it was designed to do which is, enforce the law. Again, using an ahistorical lens, the phrase “enforce the law” sounds benign and self-evident. However, for hundreds of years, laws have been written and continue to be written in a manner that explicitly or implicitly harm people of color while protecting the interests of white citizens. Police have historically been responsible for enforcing laws that, if they were in effect today, would be overt human rights violations. Imagine what it would feel like if you were expected to seek protection from and defer to people who have violated you or your family members in the past.

Historically, when police have in fact served and protected, they have enforced laws that served to protect whites from having any economic or political competition. The police have enforced laws keeping blacks from sitting where they want to on the bus, at lunch counters; from attending better schools; from living in wealthier neighborhoods. Today, laws, particularly drug laws, continue to be enforced in a manner that disproportionately targets people of color, even as whites commit more drug crime and use illegal drugs at the same rates as people of color.

The differing history and life experiences between whites and people of color in America play a prominent role in their perceptions of police today. So, while the relationship to law enforcement for whites has largely been one of respect and service, the experiences of people of color are far more ambivalent. Rather than having the privilege of viewing and experiencing police only as guardians of peace and safety, people of color ALSO view police as a threat to their well-being and safety. The history behind this perception cannot be erased, nor should it be.

Differing perceptions, histories, and experiences of white people and people of color also lead to different, logical, solutions and understandings of the issues being protested. For many people, more often white, the solution is only a matter of rooting out the overt bigots from the police force; wait for someone to do something overtly prejudiced or illegal, and then terminate them. Often times, though, police oversight is internal, ensuring that those who commit wrongdoing are protected, so long as the public does not become aware of the transgressions. And police officers who do complain are threatened, punished, or ignored for speaking out. Even so, rooting out the bigots will not change the systemic unequal treatment under the law, nor will it remove the incentives for police officers to target people of color. Yes, there are incentives, including: unaccountable seizure of property, filling beds at for-profit prisons, over-time and/or bonus pay, ensuring people of color do not feel welcome in predominantly white neighborhoods, minimizing the right to vote from those labeled ‘felons,’ thus ensuring more electoral representation for whites, among other incentives. To learn more about these incentives, read Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow.

Including history in our analysis of a problem greatly improves our ability to understand the complexity of the issue of police violence, and helps us understand that the problem goes beyond individual police officers to the recognition of a massive dysfunctional and unjust system. While individual incidents can be catalysts for actions, it is not simply the incidents themselves being protested, it is the maintenance of systems and structures that incentivize harm toward and violence toward people of color.

Understanding the systemic nature of oppression is vital to understanding how to dismantle it. Continuing to view racism as merely overt racial prejudice will ensure that nothing will change, because most people are certain they are not themselves racially prejudiced. After all, they probably have a person of color as a friend to whom they can point in order to “absolve” themselves of their own racial prejudice. Using a systemic lens allows us to see that even without overt racial prejudice, systems, structures and institutions can continue to perpetuate oppression toward people of color.

As a friend once said to me, when one thinks about racism as only being about racial prejudice it ensures that “it's not about solving the problem, it's about making sure the problem is not your fault.” We need to make sure that it is about solving the problem by exploring the systemic and structural nature of racism and dismantling it brick by brick, law by law, and policy by policy.